The conquest of ambiguity

Language is

inherently ambiguous, but the classic-prose writing style entails minimizing

conceptual ambiguity. Because precluding foreseeable confusion is the essence

of communication, the highest form of clarity is univocality (unambiguousness).

This isn’t widely understood, as this anecdote

illustrates:

In a Stanford artificial intelligence theory class, while the prof tried to present relatively precise claims, students constantly asked if he was really trying to say distantly related claims X, Y, or Z. My exasperated friend cried "Why can’t they just treat it like math – assume nothing you are not told you can assume!" ("Against Disclaimers.")

To treat natural

language as if it were an artificial language, as the anecdotal lecturer demanded,

is an unhelpful suggestion because readers can comprehend only by drawing on

information that seems relevant, and apparent relevance depends on the reader’s background information and

intelligence. But it also depends on the writer’s univocal expression. Since more

able to detect them, the intelligent reader may be particularly confused by

ambiguous cues.

The quest for

univocality isn’t confined to avoiding words with unwanted associations (and

issuing the necessary disclaimers if that isn't possible). It rests primarily

with emphasis, through means such as the new

topic/stress principle, the brevity

principle, and unobtrusive repetition. It also involves avoiding every

manner of self-contradiction.

Varieties of clarity

The great irony

in contemporary writing advice is that all extol “clarity” but none is clear on the term’s meaning. The

consequence of the nearly universal failure to appreciate the different varieties

of clarity causes writers to ignore some of them—particularly the most central,

univocality.

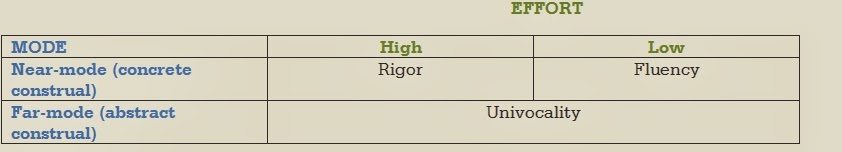

These are the

three varieties of clarity in writing and their definitions:

Fluency: Understanding the argument’s detail with

minimal effort.

Rigor: Understanding the argument’s detail with high effort.

Univocality: Conceptually unambiguous understanding

at all effort levels.

These

distinctions are pragmatic rather than logical. They describe varieties of

clarity furthered by different strategic choices, which advance one variety of

clarity and often undermine another.

Clarity and construal level

You may be

struck more by the dissimilarities between the varieties of clarity, and you

will then wonder why anyone would use the same term for all of them. The common

element in all varieties of clarity is their reference to the amount of

relevant information conveyed, the distinctions between them concerning the

amount of effort required (low or high) or the kind of information (detail or

disambiguation). One obstacle is that we seem only to think of clarity as

meaning one or another of its varieties, the most common interpretation of “clarity”

being fluency: clear writing is understood with ease.

An analogy might

help. A drawn picture will show clarity of the fluent variety when the details

can be taken in with a glance; of the rigorous variety to the extent it

contains all relevant information, leaving little to guesswork or intuition:

and of the univocal variety if it doesn’t

look like anything other than intended.

The varieties of

Clarity have a peculiar structure predictable from construal-level theory (as

I’ve construed it). The theory varieties of clarity can be generated by

crossing required effort with construal level:

Since effort—allocated

in near mode—doesn’t vary in far mode, univocality depends only on construal

level being abstract. The features of each variety of clarity point to how each

relates to effort level and construal level. Cognitive fluency is promoted by simplicity; I’ve previously discussed its limitations

and offsets.

Rigor must be applied selectively.

Readers use subjection to rigor as a guide to meaning, so being unnecessarily

rigorous about some point distorts. Rigor is governed by two of the philosopher

Paul Grice’s Maxims:

2. Don’t be more informative than is required.

Disclaimers reclaimed

Univocality is

the highest stage of clarity which—its skills developed later—comes to govern

the other varieties. I’ll conclude with the starting topic, the disclaimer,

which has been the victim of some bad connotations due to its legalistic abuse.

Disclaimers serving only to comply with (supposed) legal requirements are deplorable

from the standpoint of univocality: conceptually superfluous disclaimers are

not innocuous, as they distort the intended meaning.

Whether

due to skill limitations, audience resistance, or nuanced message, sometimes

univocality is furthered by disclaimers. Artificial intelligence, the anecdote’s

subject, exemplifies a topic subject to both resistance and preconception,

where conceptual disclaimers further univocality. An example of a disclaimer

occurs in the present entry under the subhead “Varieties of clarity”: “These

distinctions are pragmatic rather than logical.” Readers can judge whether it

was helpful.