The nature of ordinary learning isn’t itself my concern here, just the peculiar relationship

between the concretizing and abstracting mindsets. Governing this relationship

are two basic processes: suggestion and dissonance modulation. The main practical

relevance for writers is that what works for changing belief through suggestion

fails for change by dissonance modulation. For example, suggestion demands the

greatest simplicity because suggestion involves bypassing the critical faculty

(that is, the brain’s cingulate), and the easier a proposition is to

understand, the more it is accepted automatically, since acquiring disbelief necessitates

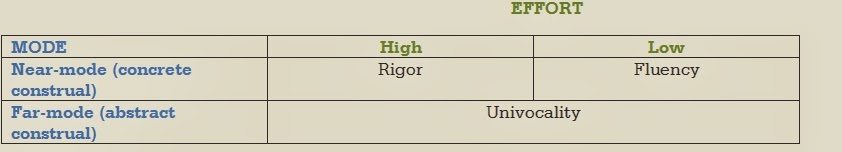

express rejection. On the other hand, effective dissonance modulation requires

univocality, since without it the recipient of the influence is likely to

achieve consonance through a different route than the persuader intends. The

difference is that the subject of suggestion submits to influence, whereas the

recipient of a communication using dissonance modulation will only accept the

writer’s ideas if they are actually dissonance reducing. Imprecision arouses

rather than resolves dissonance. As for suggestion, in hypnosis vague

suggestions work better than precise ones. (Thus, telling subjects that that

they are “going to sleep” can induce hypnosis even though hypnosis isn’t

actually much like sleep.)

Conflation of suggestion and dissonance modulation runs

deep. It isn’t just a matter of a superficial

trend in writing pedagogy; it also afflicts those whose business it is to know

better, such as social psychologists and (remarkably) specialists in hypnosis.

The bias of social psychologists reflects the orientation to advertising.

Although the theories of cognitive dissonance and construal level come from

social psychology, the classic social psychological research on persuasion,

which provides the framework for general discussions of the persuasion process,

implicitly equates persuasion with suggestion. (An equation that is actually

worth retaining if its limits are understood, inasmuch as the act of persuading others can be contrasted with

the act of convincing them, the blue

route contrasting with the green.)

The confusion is greatest within the dominant school of

professional hypnotists. The

font of clinical hypnosis (outside of hypnoanalysis), Eric Ericson, attributes

results he achieves through the artful modulation of cognitive dissonance to

some form of hypnotic suggestion. Now, here’s

confusion enough to be funny. Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams, who is a trained

hypnotist (apparently of the Ericsonian persuasion), concluded that Donald

J. Trump’s methods and results make him a “master persuader.” Perhaps

subliminally recognizing that cognitive dissonance is the key to deep rather

than superficial attitude change (which is to say, change of opinion rather

than belief), Adams took Trump’s ability to use suggestion on supporters, predisposed

to accept his influence, to prove Trump had mastered cognitive dissonance.

Adams predicted that Trump would win in a landslide because he could hypnotize

most anyone.

Lexicographers and usage experts expatiate on the

distinction between the verbs persuade

and convince. The distinct meanings

may be on the verge of loss, but it marks an important psychological

difference. According to the lexicographers, persuasion is aimed at obtaining

action, as in persuading a judge to sustain a motion. Persuasion means change in belief, without any change in opinion

being necessary. But you will rarely change a judge’s belief without changing his opinion. (The effect of

suggestion is actually obtained primarily from respective law firms’ prestige.)

So, despite the aim being to persuade judges, advocates typically must convince

them—of something. For the same reason, when academics try to persuade editors

to publish a paper, in the usual they must convince them, at least in the best

journals. Even more than when a lawyer influences a judge, the academic must

use dissonance modulation, since the practice of blind review screens out many

indicia of status that are so influential in the use of suggestion.

This is a general model of the persuasion process (more

precisely, of the processes of persuading and convincing) that highlights the

relationship between construal-level theory's abstracting and concretizing

mindsets. The two epistemic attitudes, belief and opinion, are subject to their

respective modes of influence, suggestion from belief to opinion and cognitive-dissonance

modulation, from opinion to belief. In the diagram the blue arrows represent

the path of cognitive dissonance modulation and the green arrows of suggestion.

Hypnosis is a short-cut to belief formation in that it bypasses opinion.

Post-hypnotic suggestions are incorporated into the subject’s belief system, whereas the justification is extemporized

when an explanation is requested. It may be easier to see the abstracting

character of hypnosis in terms of the corresponding time orientation. Although

hypnosis may be self-induced, the process for intentionally inducing hypnosis

is first learned in the process of being hypnotized by another person and being

given the post-hypnotic suggestion that the subject will be able to reproduce

the state. Thus the nature of the influence is interpersonally “far.” Dissonance modulation is near because it is perceived

as an internal process. It is concrete because it can be resolved into discrete

discrepancies. (Dissonance supplies a metric for overall coherence based on

discrete discrepancies, a topic to be visited in my Juridical Coherence blog.)